by Admin | Nov 19, 2013 | Highlights

Steven Greenhouse, the labor and workplace reporter for The New York Times, published an article yesterday portraying the rising tension between the European- and American-led garment multinationals in resolving workers’ issues. Boston Global Forum is honored to support Steve’s research when inviting him to join our Online Conference on November 18th, 2013.

For the original version of Steve’s article, please visit: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/19/business/international/europeans-fault-american-safety-effort-in-bangladesh.html?ref=stevengreenhouse&_r=1&

Europeans Fault American Safety Effort in Bangladesh

Published: November 18, 2013

Tensions broke into the open on Monday involving two large groups of retailers — one overwhelmingly American, the other dominated by Europeans — that have formed to improve factory safety in Bangladesh.

An official from the European group voiced concern that the American retailers would piggyback at no cost on the efforts of the Europeans — which includes H&M, Carrefour and more than 100 other retailers — in financing safety upgrades at hundreds of factories.

The members of the European-led group, the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, have made binding commitments to help pay for fire safety measures and building upgrades when shortcomings in safety are found in the more than 1,600 garment factories its members use in Bangladesh. While the American-dominated group, which has 26 members, including Walmart Stores, Target and Gap, has stopped short of making such a binding commitment, it has pledged to provide loans for the improvements.

Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium, a labor rights group based in Washington that is a member of the Europe-led accord, said members had a “significant concern about a free-rider situation.”

Jeff R. Krilla, the president of the American-dominated group, the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, said he was surprised by the criticism, noting that his alliance had agreed to make $100 million in low-cost loans available to Bangladesh factory owners to finance safety improvements.

In a sharp exchange in a telephone conference call on worker safety in Bangladesh that was organized by the Boston Global Forum, a nonprofit research organization, Mr. Krilla said his group’s members were making a significant financial commitment to improving safety, including a total of $50 million over five years in contributions by retailers in the alliance. The two groups, founded after the Rana Plaza factory building collapsed last April, killing more than 1,100 workers, are just beginning factory inspections. Despite the friction, they have been working closely together to develop joint inspection standards on fire and building safety.

Srinivas B. Reddy, director of the International Labor Organization’s office in Bangladesh, described a change in attitude among Bangladesh factory owners who have frequently been criticized by the United States and other countries for shunning safety concerns and suppressing labor unions.

“The factory owners in Bangladesh have clearly realized that unless these issues are addressed in terms of improving safety and labor rights, the industry may land in crisis,” Mr. Reddy said.

That could lead to the loss of orders from Western companies. Bangladesh is the world’s second-largest garment exporting nation after China, exporting nearly $20 billion in apparel each year.

In the conference call, Mr. Nova, in a clear reference to the American-led alliance, said that members were concerned about “the tremendous lack of worker involvement” in some factory safety efforts.

The European-led accord has two giant union federations as members with tens of millions of members, IndustriALL and Uni Global. The American alliance does not have any formal union participation, but Mr. Krilla said his alliance expected to work closely with Bangladeshi unions.

In recent months, Walmart, H&M and other retailers have sponsored their own emergency safety inspections of factories, in part to prevent any new disasters before inspections called for in the groups’ accord begin at hundreds of factories.

Late Sunday, Walmart posted on its website the results of 75 inspections that it commissioned for factories it uses in Bangladesh.

Kevin Gardner, a Walmart spokesman, said the reports showed that many factories had “made real improvements that are making the supply chain safer for thousands of workers in Bangladesh.”

Mr. Gardner said that 34 of the 75 factories had moved from having a D or C rating to having an A or B rating.

“This is the first time a retailer has published results of factory audits on this scale,” Mr. Gardner said. “We believe transparency is vital to improve worker safety in Bangladesh.”

In a separate interview, Mr. Nova criticized Walmart’s inspection reports as inadequate.

“I expected to see much more substantive detail,” he said. “They really don’t point out specific or actual hazards.”

He praised Walmart for disclosing the names of its factories, which many retailers refuse to do. “But in terms of public disclosure, it’s pretty useless,” he added. “There’s no way for workers at a factory to tell what specific hazards they face, whether it’s a lack of smokeproof enclosed staircases or something else.”

by Admin | Oct 7, 2013 | Highlights

Even though safety standards have improved somewhat, Bangladeshi factory workers are still being abused due to wage and overtime violations carried out by their supervisors. Unfortunately, this situation is caused by the flawed monitoring activities by big brand names, including the Gap Inc. VF Corp., which owns The North Face, Wrangler and Nautica, and PVH Corp., which owns Tommy Hilfiger. Clearly, these multinationals need to step up their monitoring efforts as they recently all made pledges to crack down on poor working conditions in their subcontractors’ factories.

Shelly Banjo of the Wall Street Journal has the story.

DHAKA, Bangladesh—Next Collections Ltd., one of more than two dozen factories owned by one of Bangladesh’s largest garment producers, tells buyers its workday runs from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m.

On a recent Saturday night, however, bright fluorescent lights flickered well past 10 p.m. as workers inside furiously stitched children’s skinny jeans bound for Gap Inc.’s Old Navy stores.

The company regularly keeps many of its 4,500 workers late—sometimes until 5 a.m.—to meet production targets set by retailers like Gap, VF Corp. and Tommy Hilfiger parent PVH Corp. The workers themselves sometimes welcome the extra pay, but the practice apparently conflicts with the retailers’ stated policies and a Bangladeshi law that prohibits more than 10 hours of work a day, including two hours of overtime.

Photo: Shelly Banjo/The Wall Street Journal

Photo: Shelly Banjo/The Wall Street JournalMohammad Mazharul Islam, a former worker at the Next Collections factory, where he alleges he was beaten.

The late hours at the Next Collections factory show the challenge retailers face in trying to police supply chains that can run to hundreds of factories in several countries. It also makes clear that recent pledges by retailers to crack down on poor working conditions in the wake of multiple deadly disasters in Bangladesh’s textile industry won’t amount to much without careful follow-up to monitor compliance.

Ha-Meem Group, which owns Next Collections, didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment. In an interview with The Wall Street Journal earlier this year, owner A.K. Azad said the company is eager to keep its workers happy.

Next Collections’ gray concrete compound, located along a dirt road in the congested outskirts of the Bangladeshi capital, keeps two sets of records and pay slips, according to interviews with nearly a dozen current and former workers and managers, and supported by pay documents reviewed by the Journal and a current manager at the factory group.

“It is easy, because auditors and buyers never come around late at night to check these things,” the current factory manager said in an interview. “Sometimes, it is the only way to meet the orders on time.”

From June through September, one set of computer-generated pay slips provided to buyers and reviewed by the Journal depicts a 48-hour workweek with no more than 12 hours of overtime. Another set of handwritten documents, confirmed by the current manager, outlines which workers received dinner stipends worth about 40 cents for working past 1 a.m. That set of documents appears to show that many employees were in fact routinely working more than 100 hours a week.

Photo: Shelly Banjo/The Wall Street Journal

Photo: Shelly Banjo/The Wall Street Journal

Next Collections keeps two sets of books on workers. The handwritten one logs late hours for worker 43012, not shown on the pay stub.

Many of the factory records were provided to the Journal by the Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights, a workers’ rights nonprofit based in Pittsburgh. Order and production records as well as clothing labels reviewed by the Journal show that the factory recently fulfilled orders for Gap, VF and PVH. Some of the workers interviewed for this article were referred to the Journal by the institute.

VF, whose brands include The North Face, Wrangler and Nautica, has decided to stop placing work with Next Collections after finding repeated violations of its standards on wages and hours worked, according to spokeswoman Carole Crosslin. She said VF will still place orders with other Ha-Meem Group factories.

A VF compliance officer found some of the violations during an audit in January. A review in March showed the factory had made progress, but the company pulled out after another check on Sept. 23 showed the problems had returned, according to Ms. Crosslin.

“Based on our audits of Next Collections and the unwillingness of the factory’s management to fully partner with us to meet and sustain compliance with our standards, we are planning to exit the facility,” Ms. Crosslin said.

Photo: Saima Kamal for The Wall Street Journal

Photo: Saima Kamal for The Wall Street Journal

At the Next Collections factory, lit up in the far background, garment workers are sometimes kept until 5 a.m.

Gap said it launched an investigation into possible violations of its standards in response to inquiries by the Journal last week. It has interviewed 50 current workers and management but has yet to reach a conclusion.

“Our contracts require that factory management pay overtime and abide by all local labor laws and industry standards,” spokeswoman Debbie Mesloh said. “Should these allegations prove to be true, Gap Inc. will take action, up to and including terminating its business relationship.”

A spokesman for PVH said the company’s records show it hasn’t produced at the facility since early 2011 but that it would continue to look into possible unauthorized production, such as work that is subcontracted to the factory without PVH’s knowledge.

PVH, based in New York, has signed on to an accord led primarily by European companies that sets legally binding rules for safety improvements at Bangladeshi factories funded by retailers and apparel companies. Gap and VF have joined a separate pact led by American companies that isn’t binding and will help finance improvements that will be paid for by the factory owners. Both accords set up inspection regimes that are aimed at weeding out unsafe factories.

Labor groups and safety experts say fair treatment of workers and the sorts of practices that make factories less disaster prone go hand in hand. In many deadly incidents, workers have noticed problems but were ignored by managers focused on meeting orders.

That includes the Rana Plaza garment factory, where workers were alarmed by new cracks in the building but were forced to go back to work. The collapse of the building in April killed more than 1,100 people. The incident and a series of deadly fires that have killed hundreds more have focused international attention on safety conditions in Bangladesh.

Conditions at factories like Next Collections show that even if factories add fireproof doors and shore up cracks, the economics of a garment business that awards short-term contracts to the lowest bidders means factories still face pressure to violate wage and hour policies to compete, according to Charles Kernaghan, director of Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights.

Abundant workers who are among the lowest paid in the world have helped make Bangladesh one of the largest exporters of clothing for Western consumers hooked on cheap goods. The country’s minimum monthly wage stands at 3,000 taka, or about $40. Workers have held protests across the country in an effort to raise it to about $100.

Ha-Meem Group is a big player in the industry. The group of factories is run by Mr. Azad, the former president of the Federation of Bangladesh Chambers of Commerce and Industry and the owner of a prominent Bangladeshi television station and newspaper.

Next Collections began production in 2011 to absorb orders after a fire damaged another Ha-Meem Group factory nearby. The 2010 fire at That’s It Sportswear—which was producing clothes for the Gap, PVH and J.C. Penney Co. —killed at least 27 workers and injured 100 others.

Following a public outcry, Gap, PVH and Penney sent a letter asking Mr. Azad and Ha-Meem Group to improve safety at their factories. Gap stayed with Ha-Meem Group as the textile conglomerate made improvements to its buildings and strengthened its fire safety protocols.

In the interview earlier this year with the Journal, Mr. Azad said his company was working hard to upgrade factories, especially given safety concerns following the Rana Plaza disaster. He said the company had set up an internal committee to study improvements and planned to add sprinkler systems, among other steps.

“Customers are very concerned,” he said. If there is another major factory disaster in the country, he said, “Bangladesh will be history for garments.”

Workers and managers at the Next Collections facility say they feel the building is safe. Workers say they are comfortable navigating escape routes and handling equipment in case of a fire. Doors are typically unlocked, and regular fire safety drills are conducted, they said.

Still, current and former workers at Next Collections allege that hours are long and that managers shortchange their wages, force resignations from pregnant staff, deny workers maternity and holiday benefits, and physically abuse and verbally harass employees who are found to be trying to form a labor union.

In one case, former worker Mohammad Mazharul Islam said the factory’s managing director beat him with a stick so forcefully that he spent four nights in a nearby hospital, according to his accounts and hospital records reviewed by the Journal. The 25-year-old has since started another job at a garment factory nearby.

Commitments to improve such conditions can be hard to verify.

“None of the buyers can understand what goes on when they are not there,” said Azim Sheikh, a 26-year-old ironer at the factory who says he makes about $56 a month.

by Admin | Sep 14, 2013 | Highlights

Dr Dara O’Rourke has spent the last two decades researching the environmental, social and health impacts of global production systems. His research has evolved to include the study of governmental and non-governmental strategies for monitoring and accountability and new models of public participation in environmental and labor policy. He is currently Associate Professor of Environmental and Labor Policy at the University of California at Berkeley and is the founder of GoodGuide, the world’s largest database on safe, healthy, green, and ethical products based on scientific ratings. Dr O’Rourke has published three books, and several academic articles, including the award-winning Community-Driven Regulation (MIT Press, 2004). His newest book is titled Shopping for Good

In this interview with Boston Global Forum (BGF), Dr O’Rourke discusses loopholes in factory monitoring processes, the role of subcontractors and the development and impact of GoodGuide.

Credit-www.daraorourke.com

Credit-www.daraorourke.com

BGF: When did you first realize that labor monitoring in global supply chains was an issue that needed addressing?

Dr O’Rourke: I was doing work in factories in Southeast Asia in the early 1990s but I focused more on environmental issues at that time. I worked for the UNEP in Bangkok and for my PhD dissertation I studied factories in Vietnam, starting in 1994. In 1996, I researched ten factories in Vietnam one of which was producing shoes for Nike. I conducted a waste audit technocratic environmental assessment of the factory’s conditions and found very poor environmental conditions but also discovered very poor work place environment conditions. During my research, Nike had hired Ernst & Young (EY) to audit their factories and, in addition to what we found, EY had documented that two-thirds of the women had respiratory illnesses, massive violations of overtime laws, alleged rapes of women in the factories and other horrendous kinds of physical and verbal abuse.

I spent several months interacting with Nike trying to get them to take these problems seriously but they didn’t. I ended up writing a report on the conditions in these factories which was published in The New York Times in 1997. That is what pulled me from doing technical research to being engaged in broader public debates about work place conditions. I started looking not only into technical issues about air quality within factories and chemicals and toxics used in production but broader labor rights and human rights issues. I’ve done research in the last 15 years inside factories that make global brands of footwear, apparel, toys, electronics, chemicals and processed food and have focused increasingly on interdisciplinary work that looks at the full environmental, social and health impacts of production systems. I moved from technical questions of what chemical or solvent in the shoe causes a respiratory ailment to how you can change systems of governance of these global supply chains to prevent toxics, prevent sweatshops and prevent worker abuse. I conduct research and interact with governments, NGOs, unions and companies on new governance strategies to try and improve conditions in these global supply chains.

BGF: Even with monitoring processes and audits on the ground, why have situations not improved in the last 20 years? What has prevented progressive change from taking place in factories?

Dr O’Rourke: This is the sad part, and it’s mentioned in The New York Times article that we see the same problem surfacing over and over again. It feels like I give the same interview every year or so on the failures of global regulatory systems and the failures of monitoring systems. They continue to not find the problems in these factories or they continue to not solve the problems in these factories.

In the case of Bangladesh and the current global apparel industry, I think they monitor only symptoms of problems in the industry. For example, a checklist audit can observe people working beyond legal limits so they document overtime violations or they document accident and injury rates. The monitoring process is able to identify those symptoms of problems. Our work is to find out how to go from that symptom to a root cause of a problem and answer questions like: why are these accidents occurring and when are they occurring? If they’re occurring between 12am-4am, why are the workers working at that hour? In response, factory managers may say that the order came in late from New York or San Francisco, and they had to work overnight cause the contract said that if they miss the deadline, they would have eat all the material cost and could go bankrupt. By looking deeper, you start going from the accident rate to the overtime to the real cause- which is actually a contract that specifies a delivery time, a speed of operation and a price point that drives the factory to cut costs, work laborers long hours at low pay and eliminate safety procedures. And as you dig further down into the system, I would say the real root cause is the system of fast fashion which consistently drives down prices, speeds up delivery time, increases style changes and puts pressure on the whole system downward, including on the monitoring system where you’ve got a commodity-business of checklist auditing in factories that can’t take the time to progress from symptoms to root causes to solutions for those root causes.

There is a lot of blame to go around in Bangladesh from inspectors to factory managers to corrupt government officials to the parliament itself but there’s a lot of blame in the hands of the US retailers that are specifying, through their contracts, production pricing and delivery times which I think are the root cause of why workers walked back into Rana Plaza on April 24th. Their factory managers knew that if they did not complete those orders, they could go bankrupt. The workers knew that if they did not walk back into the factory, they could lose their job. This is where I think the monitoring systems miss the root cause and focus on symptoms, and at best identify problems. But they’re almost never solve these problems.

BGF: In almost every media report, the subcontractors get blamed from both the demand and the supply end. What’s the role of subcontractors?

Dr O’Rourke: The whole system of global apparel is organized in a fashion such that due to the fast fashion industry, the people who cut the deal are not the same as the people who produce the goods. The deal is cut by big middle organizations, like Li & Fung, but often they are smaller contract or job houses that find factories to produce the goods. What we see repeatedly is that in the day after a catastrophe all the global brands and retailers are scrambling to find out if they have products being produced in those factories. The system is intentionally designed to not only outsource production, but to outsource responsibility for hiring workers, managing the supply chains and dealing with inventory. To meet delivery pressures, the first factory receiving the order illegally subs out some of the order to meet the deadline. The brands have such poor visibility into their own supply chains, that for Rana Plaza, two weeks had passed before Benetton came out and admitted that they had products in Rana Plaza. It was a week after Tazreen (factory fire) that Wal-Mart admitted it had products in Tazreen. These brands intentionally don’t know where their product is being manufactured and they intentionally want to sign a contract with a middleman who is not on the front line.

BGF: So, what’s going to happen to the middleman in the light of these disasters?

Dr O’Rourke: They’re definitely not going to be replaced. None of these brands or retailers want to manage the actual production of their products. They’re going to continue to play a key role and we’ve actually seen an increase in role and an increase in concentration of power and an increasing vertical reintegration among the very large companies. The middlemen are becoming bigger and more powerful and more important. And I would say, that going forward their brands are going to be publicly known. For example, two years ago no one had heard of Foxconn (supplier of electronics) but now Foxconn is a known entity. And the same holds true for Pou Chen (the largest shoe manufacturer in the world) and Li & Fung. I think the middleman will grow in both power and notoriety and their brands will become known brands and they will be targeted by NGOs as key actors in the global supply chain. I don’t see them going away at all; I see them getting stronger.

BGF: How do you source information to rate products according to health, environment and society factors for GoodGuide- your consumer education and information tool?

Dr O’Rourke: We have a science team that conducts ‘product oncology’ which is an assessment using several different scientific methods. We rate our products according to three categories- environment, health and society. For environment, we use life cycle assessments; for health, we use chemical risk assessments and health hazard assessments; and for society we use social impact assessments. Our team looks at a product category and comes up with what matters most on the environmental, health and social impacts across the full life cycle of that product. Our team first identifies what matters most, scientifically, and then develops a complex algorithm with hundreds of attributes, which is passed down to the data team. The data team collects data on those attributes related to the product, the company behind the product and the supply chain. We pull data from different data sources around the world covering six primary areas. These include company self-disclosures, government databases, academic data sources, private research firms, socially responsible investment communities and authoritative NGOs.

The algorithm and data collectively feeds into a process that allows us to rate products and companies on a 10-point scale with 10 being the best. We also have an engineering team that has built our website, iPhone and android apps and a toolbar browser plug-in so consumers can use GoodGuide while shopping on Amazon. We’ve built tools for consumers to help personalize their shopping. The science can be filtered through a consumer’s personal concerns. Example if someone is concerned about animal testing, they can filter out all companies that test their products on animals by using tools on GoodGuide.

The hard work is building the algorithm. Once we’ve built the algorithm, we can rate any company in the world if we can get data on them. It’s a lot of work but it’s designed to be scalable so we can rate any shampoo, any pair of jeans or any cell phone in the world.

BGF: What measurable impact has GoodGuide had?

Dr O’Rourke: We’ve had over 25 million consumers use GoodGuide, a million have downloaded our iPhone app and we have data to show the impact of GoodGuide ratings on consumer purchase and decision-making. On the company side we know from the industries that we’re interacting with, that we’re having a real impact on a number of industries especially in encouraging transparency. We’ve seen a number of industries become much more transparent than they were when we started. And once they become more transparent, we see them phasing out toxic chemicals from their ingredients. But it’s not us alone, we are part of an ecosystem of groups that are moving industries to become more transparent and hopefully phase out some of their worst chemicals and processes.

Click image to watch video on YouTube

by Admin | Sep 13, 2013 | Highlights

[For Part 2, please click here]

Boston Global Forum (BGF) had an opportunity to sit down with Professor Kent Jones of Babson College. Dr. Jones specializes in trade policy and institutional issues, particularly those focusing on the World Trade Organization. He has served as a consultant to the National Science Foundation and the International Labor Office and as a research associate at the U.S. International Trade Commission, and was senior economist for trade policy at the U.S. Department of State. Dr. Jones is the author of numerous articles and four books, including Politics vs. Economics in World Steel Trade, Export Restraint and the New Protectionism, Who’s Afraid of the WTO? and most recently, The Doha Blues: Institutional Crisis and Reform in the WTO.

BGF: As an authority on international trade, what do you think will be a possible solution to prevent another Bangladeshi tragedy from happening?

Professor Kent Jones: As any economists would point out, the problem is clear—the building’s standard was extremely poor and, thus, a possible solution must involve the improvement of building standards in factories around the world. However, this is a very complicated task to achieve, and any meaningful procedure must include leadership from multiples fronts—the multinationals, the government, humanitarian groups, NGOs, groups like Boston Global Forum and international organizations such as the ILO [International Labor Organization]. The ILO does have an international labor standard and the ability to send in teams to investigate the safety of factories. However, the problem arises when the ILO does not have enforcement authority, meaning that, even though it can raise concerns over any violations of working standards, the ILO does not have any rights to punish or sanction the respective country. The case for the WTO, however, can be more interesting. As for the idea of having the WTO address this problem, this seems to be attractive to many people, since the WTO does have the authoritative power of pressuring member countries [Bangladesh has been a member since 1995]. The procedure is as follows: if a member nation violates a WTO trade agreement, that country would have to send a representative to present in front of the WTO Dispute Settlement court in Geneva. If the country is found guilty of violating any trade codes, the WTO would allow a certain period of time for the country authority to change its policy. Eventually, if nothing happens, the WTO may then allow the country’s trading partners to raise tariff and/or other fines. Thus, it is an attractive idea that the WTO should play a role in preventing a Bangladeshi tragedy to happen again. Unfortunately, this idea will not work. First, the WTO has a very small budget [195 million Swiss Franc in 2013]. More importantly, the WTO does not protect international labor standard at the moment, and I am skeptical that any discussions to include this issue into the current code would be effective, because every time the WTO adds a certain policy, it has to receive approval from all of its 159 members.

In any cases, our best hope is to have the multinationals at the forefront of this issue, for a number of reasons, but the most important is that these brands all have images they need to keep in the eyes of the consumers. If, for example, Walmart, Macy’s and JCPenney sit down together and develop a “code standard” that requires their subcontractors to maintain the international labor standard, there is possible progress we can rely on.

BGF: You already discussed about the WTO’s role in solving this issue, how about the World Bank and the IMF?

Professor Kent Jones: These two organizations indeed have much larger budgets than the WTO and do have powers to achieve what we hope. The IMF, however, does involve in larger scale projects, for example, improving a country’s financial services sector. The WB, on the other hand, has a lot of potential to be an impactful force on the quest to improve labor standards in the countries which it provides financing.

BGF: Thank you for your time, Professor.

by Admin | Sep 11, 2013 | Highlights

Boston Global Forum (BGF) had an opportunity to speak with Arnold Zack, an Arbitrator and Mediator of over 5,000 Labor Management Disputes since 1957; former President of the Asian Development Bank Administrative Tribunal; designer of employment dispute resolution systems;; occasional consultant for the governments of the United States (Department of State, Peace Corps, Department of Labor, Department of Commerce), Australia, Cambodia, Greece, Israel, Italy, Philippines, and South Africa, as well as the International Labor Organization, International Monetary Fund, Inter-American Development Bank, and UN Development Program. He has also been a Member of Four Presidential Emergency Boards (chair of two). (Harvard Law School), and currently teaches at the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School.

BGF: Can you tell me about your background and the works you have been involved with?

Arnold Zack: I am a lawyer, a mediator and arbitrator and I have helped design dispute resolution machinery in countries including South Africa, Bermuda, Ukraine, and many other countries. In 2005, I became interested in what is happening in China. Currently, I am involved with MIT developing a project in China to train the next cadre of graduates at affiliated business schools to have a sensitivity of work place problems. I am also mostly interested in educating these graduates to be able to design machinery that can help avoid problems like the suicides at Foxconn, and which leads to tens of thousands of strikes in China each year.

Right now, I divide my time between arbitrating for corporations like AT&T and American Airlines and the project in China. I am primarily interested in helping workers live in better conditions, make more money, and lead better lives. Obviously, there has to be a balance between these issues and the legitimate claims of employers making money and having responsibilities to stockholders. Of course, the question is what a fair balance should be. However, I am less interested in figuring out where this balances lies than in developing machinery and procedure so people can negotiate and talk about those problems. Especially, I would like to enable workers the ability to feel empowered enough to peacefully resolve disputes, so that they do not have to go on strikes, get beaten, thrown into jails and lose their jobs. You have to note that there is no prescribed level as which there is an economic balance between workers and management. In fact, there are international standards and norms, but, so far, there is no legislation that mandates worldwide employers to abide by these standards.

In any cases, I hope that I can create enough public pressure and stress the self-interests of related parties to realize the benefits of developing procedures to negotiate their differences. I think the only pragmatic approach to achieve my goal is by focusing on the self-interests and to try to establish fair procedures. We have accomplished this in the US in the union management field through the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. I have been able to accomplish this task within the U.S for individual employment disputes, outside of collective bargaining. The Arbitration Act of 1925 has been used by employers to require a commitment, by new employees that, as an employment condition, they go to arbitration mandated by the employer over any employment disputes and give up their rights to appeal to court for enforcement of statutory rights. The Supreme Court case of Gilmer vs. Interstate/Johnson Lane in 1991 endorsed such mandatory arbitration. In this case, an employee, who was hired as a stockbroker, got fired at the age of 42 or so. He tried to sue the employer based on the Age Discrimination Act, but failed, as, upon signing the employment agreement, he had given up up his rights to go to court and was forced to go through an arbitration process. I believed this process was not entirely fair and we had to have a fair procedure, so I brought to the table all related parties—the management, the union, worker groups, the American Civil Liberties Union the American Bar Association, and American Arbitration Association and established a standard procedure of fairness, called “Due Process Protocol.”

I have been trying to replicate this internationally, and I had some success in developing a similar procedure in South Africa after black workers refused to join unions controlled by white workers when allowed to in 1982. The black workers organized and white employers realized it was to their benefit to negotiate with them to resolve their disputes. We developed procedures to train mutually acceptable mediators and arbitrators and make them available to disputants to minimize strikes and establish workplace procedures for negotiation. This became the model for the development of the new constitution where the partnership of worker unions, employers and the academics established a partnership to assure resolution of political conflict. That procedure has worked well until recently when it seems to have fallen apart.

BGF: You mentioned the self-interest of related parties, can you elaborate on this point—how does this relate to your efforts and how can this help address issues including the tragedy in Bangladesh?

Arnold Zack: We accept in the US that there will be a level playing fleld in which management and the designated representative of its workers will be able to meet an negotiate the resolution of their disputes over wages hours and working conditions. That is also what happened with the development of the labor law in South Africa. But the problem as it arises in an individual country is different when one focuses on the global economy, where brands and employers seek locations where they can best enhance their profit as they make their products for the global market place. With a competitive market on price, they can best maximize their profit by paying the lowest wages to workers and having them work the longest hours, particularly if the host government turns its head, accepts bribes to avoid enforcement of their national labor laws and keeps workers from organizing into a single voice to express their demands.

The concept of employees having freedom of association and the right to engage in collective bargaining is one which is enshrined not only in the UN Human Rights Charter, it is also an international norm established by the Conventions of the ILO. In our global economy, the quest of employers seeking to produce their products at the lowest possible cost to enhance their profits, has too often led them to South East Asia where workers receive the lowest wages, and have the least protection from their own national governments. What transpired in Bangladesh with its garment factory fires is just the most recent example of the extent of such exploitation despite the availability of international norms trying to establish workplace fairness. As noted earlier the ILO establishes norms, but most nations do not enforce them within their own laws and too many countries are so corrupt that they disregard the safety as well as the workplace rights of their citizens to pocket a little more money from the contracting factory owners. The world has tended to rely on the brands to monitor these factories, although the evidence increasingly shows they cant or wont do that, turning a blind eye to the corruption and worker exploitation. There is one example to the contrary, however, Cambodia, where the ILO Itself does the monitoring, and where a separate organization the Arbitration Council provides mutually acceptable arbitrators to resolve disputes over whether there has been conformity to contract and law seeking to achieve compliance with ILO conventions. . The experience there since 2002 has lead to an expansion of the garment factories, a spread of the system to construction and tourist industries, an increase in the number of unionized employees as part of an expanding work force, and all with a notable decrease in strikes and work stoppages.. Unfortunately the Cambodian experiment has not been widely replicated because of the cost involved, but it is a beacon of what can be done with international will, national cooperation and open mindedness by the employers recognizing that they do better, and make more money when their operations are conducted smoothly without strike interruption and with machinery in place to forestall workplace disruption

Going back to our China story, the self-interest of the workers is to have fair working conditions. In the Foxconn case, a worker committed suicide because she was begging for a couple of days off to go see her brother but such leave was not approved. That case was just one of a dozen suicides. Thus, you see how the workers’ self-interest is simply being able to express themselves through a process of negotiation with the management. The United Nations Human Rights Convention gives workers the right to freely associate and to bargain collectively with management on their working conditions, wages, etc., so the workers should really have the right to get to a negotiation table and talk to their employers.IT is only logical that they strike when they are denied that basic human right. On the other hand, the self-interest of brands like Apple, Nike and Honda is to produce their products on time and sell them overseas without interruption in the workplace. Let’s take Apple, for example. Apple does not want their stockholders to say that they mistreat workers and then to decide not to invest in the company. Apple has an impact on Foxconn, but it’s also in the self-interest of the contractors like Foxconn to balance their desire for maximized profits against maintaining Apples confidence and contracts. Since , if Apple pulls out of China, Foxconn would go bankrupt. Besides, it’s also in the self-interest of the Chinese governments that these brands stay in the country to provide work and income for the Chinese citizens.

Thus, what I do now is basically to go around the world and tell these parties that it is in their self-interests to provide fair working conditions. When I was in Shanghai to speak with the American Chamber of Commerce there, plant managers asked how we could stop these strikes, and I told them that you could control these strikes by listening to and negotiating with the leaders speaking on behalf of the workers. They responded saying that the law did not require them to do so. In fact, even though China is a collective society, there is no room for workers to select their own unions or union leaders, The officially recognized unions are those organized by the ACTFU (All-China Federation of Trade Unions). Thus, the problem arises when workers believe the ACTFU does not represent them. Despite having legal and contractual rights as individuals, workers, when they unite and start demanding improved conditions, higher wages and the like, do not have any established vehicles or laws that require employers to sit down and talk to them, even though the ILO (International Labor Organization) Conventions of 87 and 98 state that workers have to rights to organize into unions and the right to bargain collectively with their employers.

Let’s look at an example of what has been happening in China to gauge the power of these spontaneous strikes of workers organizing collectively. In 2010, when Honda workers went on strike and demanded a 30% increase in their payroll, the managers compromised and gave them 20%. After that, they went back on strike again and got the remaining 10% they demanded. In most parts of the world, workers have peaceful rights to organize themselves and employers have the obligations to start negotiating. Only when this procedure fails do the employees then go on strike to exercise power to get the employer to change its position. In China and Vietnam however, it actually works backwards, the workers have to go on strike first to demand the employers to come to the table so they can talk to employers. This is the reason why I am collaborating with the business schools in China to install into the existing curricula crucial topics including negotiation, ethical standard of labor conditions and fair procedures. In addition, we’re also successful in getting a local university to establish an independent center to educate workers on topics such as peaceful resolution and the economics of running a business, as an average worker may not understand the economics of overhead, profit margin, wages, and etc.

Besides, it is also understandable why China would be skeptical of some procedures which would give workers the right to elect their own leaders, as the fall of the Soviet Union is often traced to the Solidarity Movement in Gdansk Poland where Lech Walensa led the establishment of a real trade union insisting on the right of workers to negotiate with their employer in that case the government owned ship yards. At the moment, the Chinese government does not allow workers to form their own unions. However, I believe the risk of losing foreign direct investments would outweigh the risk of opening the door for more democratic procedures at the workplace. Also, the government, so far, has not done anything to restrict us from entering the country. I am also trying to convince them that this is a practical method to resolve the problems of wildcat strikes, managers being taken hostage and other examples of frustrated workers seeking to gain a seat at the table to discuss their working conditions with management. I believe it is also in the self interest of the ACFTU to shift its role from one of monitoring the workplace to a role of representing the workers in peaceful negotiations with their employers.

This is not complex science; it is merely recognition that all the players in the economy have priorities of self interest and achieving “more” as they define that term even if at the expense of other players in their arena. But when the power is so lopsided that some of the players are excluded, or worse exploited, society owes it to all those involved to assure some measure of equity and fairness. In the world of factory work the world standard has been to permit employees if they so choose to band together as an entity that is more compatible to the power of the employer, and that standard as proclaimed by THE UN Charter and ILO conventions has been to encourage peaceful negotiations between the two parties as a better alternative to exploitation and workplace disruption through strikes. All I have been trying to do in the US and abroad is to encourage the parties to recognize that their self interest is best satisfied by recognizing that the other side likewise has self interests and that negotiations is the most rational means of resolving their conflicts. To the extent that I get people to listen to me, that is a satisfying reward. To the extent that they ask me to help them develop procedures to cope with these problems it is a reward not only for me but for the parties and society as a whole.

by Admin | Sep 10, 2013 | Highlights

In light of the tragedy at the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh, the world is scrambling to help the survivors and commemorate the victims. Let us visit the place where it all began and hear the aftermath story from the Director of the International Labor Organization (ILO) office in Dhaka.

The ILO’s branch in Bangladesh has the story.

© Munir Uz Zaman / AFP

A number of initiatives have been launched in response to the Rana Plaza building collapse in Dhaka, Bangladesh, which expand upon ILO action following previous accidents in the country. The Director of the ILO Office in Dhaka, Srinivas B. Reddy, explains what these initiatives are and the steps that have been taken on the ground.

What action has been taken during the past three months?

Since April 24, when the Rana Plaza building collapsed, claiming 1,127 lives and injuring many more, the ILO has played a lead role in seeking to address the root causes of the disaster and help rehabilitate injured victims. We are working closely with the Government and employers’ and workers’ organizations (the ILO’s tripartite constituents), to help improve workers’ rights and safety in the ready-made garment (RMG) sector.

In the immediate aftermath of the accident, the ILO sent a high-level mission to Dhaka, headed by the Deputy Director-General for field operations, Gilbert Houngbo. The result of the mission was aJoint Statement, signed on May 4, by the Government and employers’ and workers’ organizations, which set out a six-point response agenda.

What does the response agenda consist of?

The Joint Statement committed the Government of Bangladesh to submitting a set of amendments to its Labour Law, which it did on 15 July, and ILO has commented on it. The response agenda also requires an assessment of all the active RMG factories for fire safety and structural integrity, as well as measures to fix the issues discovered. It also commits the government to recruit, within 6 months, 200 additional inspectors and to ensure that the Department of the Chief Inspector of Factories and Establishments will have been upgraded to a Directorate with an annual regular budget allocation adequate to enable the recruitment of a minimum of 800 inspectors and the development of the infrastructure required for their proper functioning.

It recommends expanding the existing National Tripartite Action Plan on Fire Safety, signed after the Tazreen Fashions factory fire in November 2012. Progress has already been made through an agreement reached on July 25 by the Government, employers and workers to integrate this plan and the Joint Statement to form a comprehensive National Tripartite Plan of Action on Fire Safety and Structural Integrity in the RMG sector.

For those directly affected by the Rana Plaza collapse, a skills training and rehabilitation programme will be launched for those disabled by the disaster and those who were left unemployed.

The Joint Statement also called on the ILO and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) to consider launching a Better Work Programme for Bangladesh. Better Work is a partnership programme between the ILO and the IFC, which aims to improve both compliance with international labour standards and competitiveness in global supply chains.

How does this plan fit with the other response initiatives established by brands, retailers, global unions and other institutions since April?

These emerging response initiatives have endorsed and echoed the now integrated National Tripartite Plan of Action on Fire Safety and Structural Integrity (NTPA) and, in several cases, the ILO’s technical support has been asked for to help ensure their implementation and coordination.

For example, the ILO fulfills the role of neutral chair of the Accord on Fire and Building Safety, signed by global unions and over 80 fashion brands and retailers. The Accord is a five-year programme aimed at ensuring health and safety measures, including the assessment and remediation of structural integrity and fire safety in factories used by the signatories.

Another initiative, the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, brings together 17 US retailers and brands and aims to inspect and set safety standards in 100 per cent of the factories used by the signatories over the next 5 years.

The Sustainability Compact, between the EU, Bangladesh Government and the ILO, published in July, builds on the NTPA and seeks action on labour rights, in particular freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining, building structural integrity and occupational safety and health, as well as responsible business conduct by all stakeholders engaged in the RMG and knitwear industry in Bangladesh.

The Compact has assigned a coordinating and monitoring role to the ILO. Coordination between these various initiatives will be vital, to ensure they have the desired impact.

These plans sound good in theory but what tangible action has been taken so far?

For its part, the ILO Office in Dhaka is implementing a US$ 2 million, six-month programme from July to December this year.

The first element is assisting the constituent partners in establishing a system to undertake a preliminary assessment of the safety of factory buildings. The ILO will work with the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) to train 30 specialist teams of structural engineers to undertake these assessments.

In parallel, workers in ready-made garment factories will receive safety training and those injured during the disaster and in previous accidents will begin to receive rehabilitation and skills training.

During the last three months, the ILO has also developed a broader three-year programme to take these actions forward and provide support to several key components of the National Tripartite Action Plan on Fire Safety and Structural Integrity.

This includes ensuring structural integrity assessments by trained engineers of the almost 2,000 factories not covered by the Accord and Alliance and the purchase of necessary equipment. It will also involve training of the 800 labour inspectors referred to earlier and worker and management training in occupational safety and health and worker rights.

Is this the first time that the ILO has worked in this area in Bangladesh?

We have in fact been working closely with the Government and employers’ and workers’ organizations for some time on labour conditions in the garment industry.

For example, since January 2012 a dedicated project on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work has focused on improving workers’ rights in Bangladesh, particularly in the RMG sector. It has worked with the ILO constituents to improve labour legislation and practices in Bangladesh and to develop labour relations based on rights and responsibilities.

Technical experts from the ILO office in Dhaka have been working closely with the Government during the last year on amendments to the country’s labour law, with a view to bringing it into line with international labour standards.

As previously mentioned, we also promote safer work places and have assisted the Government and social partners in developing the national response to the Tazreen factory fire in November 2012. ILO projects have also produced a fire safety video designed to be shown to and understood by all factory workers in the country and is working on a number of outreach efforts to improve knowledge of occupational safety and health best practices.

What are the next steps in the response?

We will work closely with the Government and employers’ and workers’ organizations as they implement the National Tripartite Action Plan on Fire Safety and Structural Integrity in the RMG sector, over the coming weeks and months.

A priority will be to help ensure that skilled engineers are making initial structural integrity and fire safety assessments of garment factory buildings. These will be undertaken by the engineering teams led by BUET and will be underway by September.

Skills training of disabled workers, in partnership with the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), will also be up and running and we will help coordinate services to injured and unemployed Rana Plaza victims through the National Skills Development Council Secretariat.

Training programmes for trade union leaders, mid-level managers and supervisors on occupational safety and health and workers’ rights are also due to begin, along with training to strengthen the labour inspection system.

The ILO will continue to engage with the government and its other constituents with regard to the legislative framework.

by Admin | Aug 27, 2013 | Highlights

In response to the worst factory disaster in Bangladesh’s history, the country will start surveys of over 2000 factories on September 15, 2013. The Daily Star has the story.

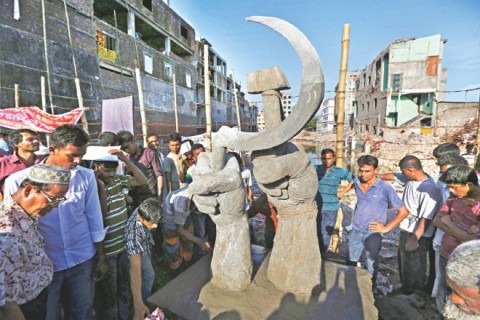

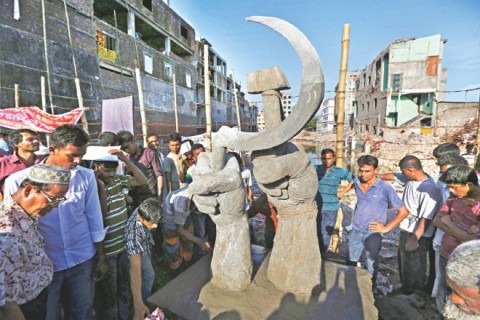

Activists and the relatives of missing garment workers gather on August 2 in front of a sculpture made by members of labour organisations at the site of collapsed Rana Plaza in Savar. Photo: REUTERS/FILE

Factory Survey Starts on September 15

Thirty expert panels led by Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology will start inspection of garment factories from September 15 to check structural flaws and ensure worker safety, a government official said yesterday.

The teams will inspect around 2,000 garment factory buildings in three months under a tripartite agreement between the government, trade unions and the International Labour Organisation, Labour and Employment Secretary Mikail Shipar said.

The inspection teams have already been formed with experts from other universities, the ILO, donor agencies, trade unions, Bangladesh Employers’ Federation, Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association, and Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association.

The tripartite agreement was signed in two phases on February 20 and July 25 after two deadly factory accidents — Tazreen Fashions fire on November 24 last year and Rana Plaza collapse on April 24.

“We will inspect the buildings, which were not included on the lists of IndustriALL and North American Alliance, to avoid repetition,” Shipar said. IndustriALL — a global trade union, and North American Alliance — a platform of 20 US-based retailers and brands for worker safety in Bangladesh, will separately inspect 800 and 1,200 factories. IndustriALL will inspect the factories under an accord signed by 85 retailers and brands, mostly European.

However, Shipar could not say when IndustriALL and North American Alliance will start the inspection. Buet will train the inspection teams from August 28, the secretary said, adding: “We will also prepare a checklist and a guideline for factory inspection on September 7.”

The labour and employment ministry has already recruited four inspectors and will appoint 72 more by October, Shipar said.

A process is underway to appoint 128 inspectors in November, he added.

Sekender Ali, a professor at Buet, said more than 200 factories will not come under the tripartite inspection as those have already been visited by experts after the Rana Plaza collapse. However, Ali is unsure whether these 200 factories will be inspected by IndustriALL and the North American Alliance.

Roy Ramesh Chandra, general secretary of IndustriALL Bangladesh Council, said they received 57 applications for the post of chief executive officer to conduct the inspection.

“We will appoint both global and local CEOs soon to start our function,” he said.

IndustriALL will open an office in Dhaka and the 85 retailers and brands will pay $12.5 million each in the next five years for the inspection and as compensation to workers. The North American Alliance has already appointed former US under-secretary of state Ellen Tauscher as the independent chair of its board of directors to start the inspection.

by Admin | Aug 21, 2013 | Highlights

Interestingly, the fire and collapse in Bangladesh’s garment factories in the last year, have not initiated a relocation of supply chain production for major apparel retailers. In this Reuters story, the sad truth that led to compromised safety standards, still seems to prevail- Cost is still King.

An employee sorts newly finished T-shirts at the Estee garment factory in Tirupur in Tamil Nadu June 19, 2013. Credit-REUTERS/Mansi Thapliyal

(Reuters) – With knitwear exports of over $2 billion a year, India’s garment manufacturing hub Tirupur has earned the nickname “Dollar City,” but its allure for price-conscious global retailers obsessed by discounts of as little as one U.S. cent pales before Bangladesh.

Indian and Southeast Asian apparel manufacturers had hoped the orders would come flooding in, after the deadly collapse of a Bangladesh garment factory complex this year galvanised global brands such as Hennes & Mauritz AB (H&M) (HMb.ST) to consider relocating production.

But several industry organisations and factories contacted by Reuters in Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and India – Asia’s top apparel makers outside China – said international retailers were not beating a path to their door just yet. When it comes to price, Bangladesh is king.

“The reason Bangladesh went from zero to hero in the garment sector is because there is no country with such low labour and other costs,” said Arvind Singhal, chairman of India-based retail consultancy Technopak Advisors.

“No buyer is in a hurry to move from Bangladesh because Western retailers are stressed about passing any retail price increases to customers,” he said. “Currently, there is no substitute for Bangladesh, where manufacturers even risk operating from rickety structures to cap costs.”

Wal-Mart Stores Inc (WMT.N) has stood by its Bangladesh production, saying the South Asian nation remains an important sourcing market. H&M also said its quest for alternative manufacturers was not at the expense of Bangladesh.

“We are not reducing our purchases from Bangladesh. We aspire to have long-term relations with our suppliers,” H&M spokeswoman Elin Hallerby said. “We are always looking at new production capacity to support our continuous expansion.”

The latest data from Bangladesh highlights its enduring appeal: garment exports in June rose 26 percent year-on-year to $2.2 billion.

COST IS KING

More than four million people, mostly women, work in Bangladesh’s clothing sector, making it the second-largest global apparel exporter behind China.

The world’s biggest fashion retailers, Inditex SA (ITX.MC) and H&M, as well as Wal-Mart, Gap Inc (GPS.N) and JC Penney Company Inc (JCP.N) are a few of the brands manufacturing there.

The $21 billion-a-year industry has been built on low wages, government subsidies and tax concessions from Western countries. But the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory complex outside Dhaka in April raised concerns about safety loopholes. The disaster, one of the world’s worst industrial accidents, killed 1,132 people.

The collapse prompted global brands to consider tapping regional alternatives.

Indonesian textile firm Sri Rejeki Isman PT (Sritex) (SRIL.JK), which makes clothing for Zara, H&M and other brands, said it was in talks with H&M about taking over an as yet unspecified amount of Bangladesh-sourced production. H&M declined to comment.

But as large factory owners across the region discovered, translating talks into orders is difficult as, compared to Bangladesh, they are considered too expensive.

“Garments produced in Bangladesh have a very competitive price, around two-to-three times lower than in Vietnam,” said Nguyen Huu Toan, deputy director of SaiGon 2 Garment JSC, a Vietnam factory whose clients include British fashion retailers New Look and TopShop.

The cost disadvantage also impacts Sri Lanka’s $4 billion-a-year garment industry, and factory owners there say any shift in production from Bangladesh will be transient.

“We are much better than any other country in the region, but it is a temporary advantage,” said Tuly Cooray, the secretary-general of industry group Joint Apparel Association Forum. “At the end of the day, the price is going to matter.”

NOT CUT FROM THE SAME CLOTH

The economic slowdown in Europe and the United States has made retailers all the more keen to seek out the lowest-cost manufacturing centres to keep their store prices down.

N. Thirukkumaran, owner of Tirupur-based apparel maker Estee which racked up $8.3 million in sales last year, said he holds marathon haggling sessions with foreign customers demanding discounts as little as one cent per unit.

At least one U.S. retailer asked about moving production from Bangladesh, he said, but they have yet to place orders. Thirukkumaran would not name the brand, citing client confidentiality.

“There are positive signals from buyers, but they are still sceptical about price,” he added.

Monthly minimum salaries for garment sector workers in Bangladesh average around $38, far below the $100 average for Indian factory workers.

After the Rana Plaza collapse, the cabinet approved changes to the labour laws that pave the way for garment workers to create trade unions without the approval of factory owners.

The cabinet also formed a wage board to consider pay increases. But industry experts say Bangladesh has too much to lose by alienating global retailers, which means that for now, the low costs are here to stay.

“No other destination has what we have and that is skilled and cheap labour,” said Mohammad Mujibur Rahman, a Bangladeshi academic leading factory inspections.

“Foreign buyers realize this and nobody is in a hurry to move out … there might be a small trickle outside, but nothing significant that will hurt us.” (Additional reporting by Nandita Bose and Ruma Paul in DHAKA, Shihar Aneez in COLOMBO, Nguyen Phuong Linh in HANOI, Fathiya Dahrul in JAKARTA, Jessica Wohl in NEW YORK, Anna Ringstrom in STOCKHOLM; Writing by Miral Fahmy and John Chalmers; Editing by Ryan Woo)

by Admin | Aug 21, 2013 | Highlights

On August 20, 2013, the American alliance elected an Ellen O’ Kane Tauscher as the independent chair of its board of directors, and also welcomed three new members- Costco, Intradeco Apparel and Jordache Enterprises, bringing the total up to 20 retailers and apparel brands. Read more in this story from just-style.com.

Ellen O’Kane Tauscher. Source- Wikimedia Commons

US: Bangladesh Safety Alliance Names Chair as Talks Begin

The group of leading retailers and brands who make up the North American Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety has named Ellen O’Kane Tauscher as the independent chair of its board of directors.

The Alliance also said it has been joined by three more companies – Costco, Intradeco Apparel and Jordache Enterprises – bringing the total to 20 apparel companies, retailers and brands.

With the new members, more than US$45m has been committed to administer the programmes developed by the Alliance over the next five years to help improve factory safety conditions for garment workers in Bangladesh.

A two-day board meeting is now underway in Chicago, where members will be briefed on progress toward several milestones taking place next month, including development of a common Fire and Building Safety Standard and Inspection Protocol, and the fire and safety training curriculum that will be given to factory managers and employees.

In September, the Alliance expects to announce the selection of its operating team, including the executive director for the programme.

Leading the board of directors, Tauscher is a seven-term member of Congress and has worked for the US Department of State. She was appointed by president Barack Obama as under-secretary of state for arms control and international affairs, serving in the role from 2009-2012.

When she returned to the private sector in 2012, she joined Baker Donelson Bearman, Caldwell & Berkowitz PC, in Washington DC as strategic advisor to clients in national security, defence, transportation, export control and energy policy areas.

“The respect Ellen has earned in Congress, the State Department, and the private sector will serve her well in the role as an independent leader and convener who can work with Alliance members and governments to pursue the critical safety mission and aggressive implementation schedule,” said Ambassador James Moriarty, an Alliance board member and former US Ambassador to Bangladesh.

The board also includes three other stakeholder representatives, including Mohammad Atiqul Islam, president of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturing and Exporters Association (BGMEA); Randy Tucker, global leader of the fire protection and safety team at CCRD, a Houston-based engineering firm; and Muhammad Rumee Ali, managing director of enterprises at BRAC, the international NGO founded in Bangladesh.

Four Board members from Alliance companies include: Daniel Duty, vice president of global affairs for Target; Jay Jorgensen, senior vice president and global chief compliance officer forWal-Mart Stores Inc; Tom Nelson, vice president for global product procurement for VF Brands; and Bobbi Silten, senior vice president of global responsibility for Gap Inc and president of Gap Foundation.

Other retailers and brands that have signed up to the Alliance include: Canadian Tire Corporation; Carter’s; The Children’s Place Retail Stores; Gap; Hudson’s Bay Company; IFG; JC Penney; The Jones Group; Kohl’s Department Stores; LL Bean;